Calcium: Building Better Bones and More

Calcium is the most abundant mineral in the human body and it’s essential for building and maintaining strong bones. In fact, 99% of all the calcium in your body is stored in your bones, where it plays an important role in supporting a strong skeleton.

From childhood until about age 30, your body uses the calcium absorbed from the foods you eat to maximize your bone mass and bone density. After age 30, however, bones gradually begin to lose calcium, making it essential to obtain enough of this nutrient, especially as you age. (21)

Immune Support Top Picks & Helpful Products to Stay Healthy

Getting enough calcium through dairy and other calcium-rich foods during childhood can help maximize your bone mass and density.

Why do I need calcium?

Although calcium is best known for its bone-building properties, this mineral plays a role in many other body functions. Every cell in your body needs calcium to function properly. (17) Calcium is involved in proper blood clotting. It’s also involved in contracting and dilating your muscles and blood vessels, carrying messages between your brain and the rest of your body, and releasing hormones. (22)

Did you know? Vitamin D helps maintain normal calcium levels by increasing its absorption within the intestinal tract. (6)

What are the health benefits of calcium?

Given that calcium plays a role in so many functions throughout the body, it’s no surprise that it confers a number of health benefits.

Bone health

Although calcium assists in building strong bones during childhood, making sure you maintain adequate levels as an adult can help keep them healthy for a lifetime. If you don’t get enough calcium from your diet or supplements, your body will take what it needs from your bones to ensure normal cell function. This can lead to osteoporosis, a bone disease that affects approximately 10 million Americans.

Our Top Picks Immune Support Protocol Package

(23) Older adults are especially vulnerable to calcium deficiency and bone loss, potentially due to a diet low in calcium-rich foods and the use of acid-reducing medications such as proton pump inhibitors. (13) (14) However, it is possible to maintain bone health throughout your life by eating plenty of calcium-rich foods, taking a calcium supplement if needed, and getting regular weight-bearing exercise. (2)

Did you know? Combining calcium with magnesium and zinc enhances calcium absorption and supports bone building cells, known as osteoblasts, while inhibiting cells that foster the breakdown of bone, known as osteoclasts. (28)(30)

Adequate calcium levels in the brain may help protect against memory loss as you age.

Brain health and memory

Calcium also plays an essential role in how your brain cells communicate with each other, which aids in cognition and memory retention. When a chemical signal arrives at a brain cell (a neuron), calcium transports the signal from the outside of the cell to the inside.

This action signals the neuron to release neurotransmitters, which are chemical messengers involved in cellular communication. (11) To accomplish this, the amount of calcium that enters neurons must be tightly regulated. Too little can impair memory, (9) while too much can damage neurons and negatively impact both memory and cognition. There is some evidence that an overabundance of calcium in the brain may even play a role in Alzheimer’s disease. (24)(25)

Colon support

Low calcium levels have been associated with a higher risk of colon cancer. The good news? Studies suggest that increasing dietary and supplemental calcium intake may lower your risk of colon cancer by as much as 25%. (10)(12)

Heart protection

Calcium supports heart health in a number of ways. One way it does this is by supporting healthy cholesterol levels. (5) Calcium may also help lower the risk of high blood pressure in middle age and older women.

(29) During the Iowa Women’s Health Study, researchers found that postmenopausal women with the highest blood levels of calcium from foods and/or supplements had a lower risk of ischemic heart disease, a condition characterized by narrowed arteries and reduced blood flow throughout the body.

(3) This is particularly important since postmenopausal women are at an increased risk for cardiovascular disease. (8)

Skin health

Calcium is critical for healthy skin. Studies show that this mineral may help individuals achieve a healthier complexion from the inside out by supporting the skin barrier and proper skin turnover. Calcium regulates skin barrier function, preventing harmful pathogens from breaching the top layers of your skin. (1)(19)

Did you know? While adding calcium to your diet via food and supplements was long thought to increase the risk of aged-related macular degeneration (AMD), recent findings show that older people with a higher calcium intake actually had a lower risk of developing late-stage AMD. (24)

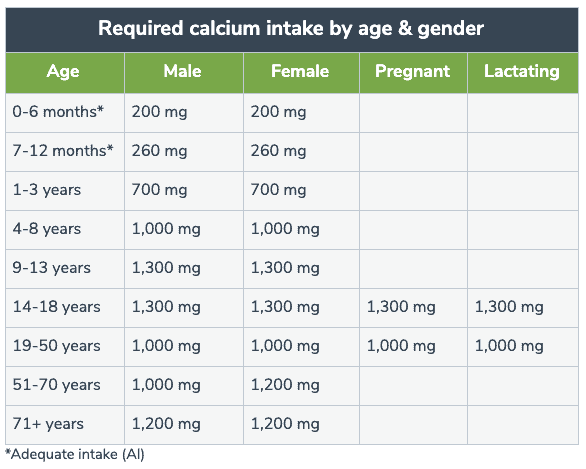

How much calcium do I need?

The amount of calcium your body requires varies, depending on your age and whether you’re a man or a woman. Below is a quick reference chart outlining daily calcium requirements for difference populations.

Calcium requirements vary based on individual needs. (22)

While most people can obtain adequate amounts of calcium from their diet, some may require extra calcium through supplementation. For instance, women lose 3% to 5% of their bone mass during the first five years after menopause, partly attributed to reduced estrogen levels, which increases the breakdown of bone, a process known as bone resorption, and decreases calcium absorption.

(4) Vegetarians also may need additional calcium because they typically restrict their intake of dairy products and consume plant foods high in oxalic and phytic acids, (27) two plant compounds that can block calcium absorption. People who avoid dairy due to lactose intolerance may also find that they are not meeting their calcium needs. (15)

Adequate calcium levels in the brain may help protect against memory loss as you age.

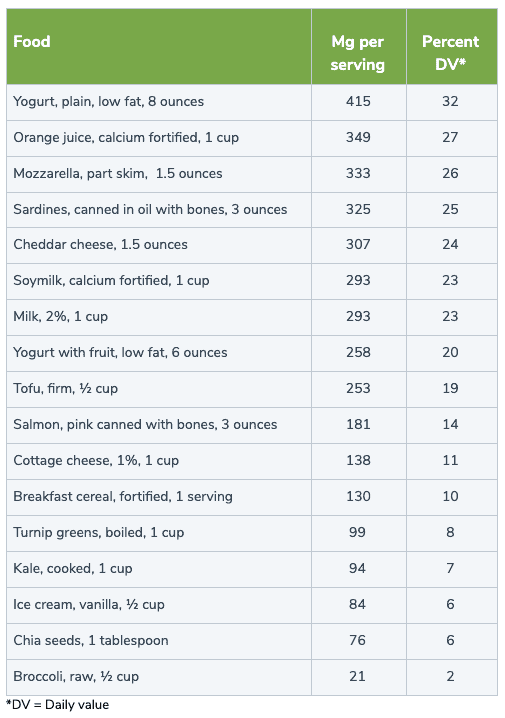

Which foods are high in calcium?

When people think of calcium, most often they think of dairy. Yet there are a number of other dietary sources that are also rich in this key nutrient. The table below highlights some of the best sources of calcium that you may want to consider including in your diet.

In addition to dairy products, there are many other calcium-rich foods from which to choose. (22)

Can I have too much calcium?

As beneficial as calcium is, you can get too much of a good thing. High concentrations of calcium in the blood, a condition called hypercalcemia, can increase the risk of kidney stones and, in severe cases, contribute to kidney failure and irregular heartbeat. (7)(18)(20) Consistently high levels may also cause confusion and play a role in dementia. (16)

The bottom line

Calcium is an essential mineral involved in a number of bodily functions. Making sure you get enough not only protects your bones and teeth, but also your brain, colon, heart, and even your skin. While it’s always best to get calcium through food, supplements can help ensure you’re meeting your daily needs, particularly if you are postmenopausal, avoid dairy products, or have low levels due to other factors. Be sure to consult with your integrative healthcare professional to determine if calcium supplementation is right for you.

Source(s) Fullscript

REFERENCES

- Adams MP, Mallet DG, Pettet GJ. (2015). Towards a quantitative theory of epidermal calcium profile formation in unwounded skin. PLOS ONE, 10(3), e0123823.

- Beto, J.A. (2015). The role of calcium in human aging. Clinical Nutrition Research, 4(1), 1-8.

- Bostick RM, Kushi LH, Wu Y, et al. (1999). Relation of calcium, vitamin D, and dairy food intake to ischemic heart disease mortality among postmenopausal women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 149(2), 151-161.

- Bregslau NA. (1994). Calcium, estrogen, and progestin in the treatment of osteoporosis. Rheumatoid Diseases Clinics of North America, 20(3), 691-716.

- Chai W, Cooney RV, Fanke AA, et al. (2013). Effects of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on blood pressure and serum lipids and carotenoids: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Annals of Epidemiology, 23(9), 564-570.

- Christakos S, Dhawant P, Porta A, et al. (2011). Vitamin D and intestinal calcium absorption. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 347(1-2), 25-29.

- Craven BL, Passman C, Assimos DG. (2008). Hypercalcemic states associated with nephrolithiasis. Reviews in Urology, 10(3), 218-226.

- Crawford SL & Johannes CB. (1999). The epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 84(6), 1803-1812.

- Drago I & Davis RL. (2016). Inhibiting the mitochondrial calcium uniporter during development impairs memory in adult drosophila. Cell Reports, 16(10), 2763-2776.

- Flood A, Peters U, Chatterjee N, et al. (2005). Calcium from diet and supplements is associated with reduced risk of colorectal cancer in a prospective cohort of women. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 14(1), 126-132.

- Gareri P, Mattace R, Nava F, et al. (1995). Role of calcium in brain aging. General Pharmacology, 26(8), 1651-1657.

- Han C, Shin A, Lee J, et al. (2015). Dietary calcium intake and the risk of colorectal cancer: a case control study. BMC Cancer, 15, 966.

- Heaney, R.P., Gallagher, J.C., Johnston, C.C., Neer, R., Parfitt, A.M., & Whedon, G.D. (1982). Calcium nutrition and bone health in the elderly. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 36(5), 986-1013.

- Heidelbaugh, J.J. (2013). Proton pump inhibitors and risk of vitamin and mineral deficiency: evidence and clinical implications. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Therapy, 4(3), 125-133.

- Hodges JK, Cao S, Cladis DP, et al. (2019). Lactose intolerance and bone health: the challenge of ensuring adequate calcium intake. Nutrients, 11(4), 718.

- Kern J, Kern S, Blennow K, et al. (2016). Calcium supplementation and risk of dementia in women with cerebrovascular disease. Neurology, 87(16), 1674-1680.

- Kinjo TG & Schnetkamp PPM. (2000-2013). Ca2+ chemistry, storage and transport in biologic systems: an overview. Madame Curie Bioscience Database.

- Landstrom AP, Dobrey D, Wehrens XHT. (2017). Calcium signaling and cardiac arrhythmias. Circulation Research, 120(12), 1969-1993.

- Lee SE & Lee SH. (2018). Skin barrier and calcium. Annals of Dermatology, 30(3), 265-275.

- Moysés-Neto M, Guimarães FM, Ayoub FH, et al. (2006). Acute renal failure and hypercalcemia. Renal Failure, 28(2), 153-159.

- National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. (2020). Calcium: Fact sheet for consumers

- National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. (2020). Calcium: Fact sheet for health professionals.

- National Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporosis Fast Facts. https://cdn.nof.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Osteoporosis-Fast-Facts.pdf

- Pereda D, Al-Osta I, Okorocha A, et al. (2019). Changes in presynaptic calcium signalling accompany age‐related deficits in hippocampal LTP and cognitive impairment. Aging Cell, 18(1), e13008.

- Small DH. (2009). Dysregulation of calcium homeostasis in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochemical Research, 34, 1824-1829.

- Tisdale AK, Agrón E, Sunshine SB, et al. (2019). Association of dietary and supplementary calcium intake with age-related macular degeneration: Age-Related Eye Disease Study Report 39. JAMA Ophthamology, 137(5), 543-550.

- Tucker KL. (2014). Vegetarian diets and bone status. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100(S1), 329S-335S.

- Uwitonze AM & Razzaque MS. (2018). Role of magnesium in vitamin D activation and function. The Journal of the American Osteopath Association, 118(3), 181-189.

- Wang L, Manson JE, Buring JE, et al. (2008). Dietary intake of dairy products, calcium, and vitamin D and the risk of hypertension in middle-aged and older women. Hypertension, 51(4), 1073-1073.

- Yamaguchi M. (2009). Role of nutritional zinc in the prevention of osteoporosis. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, 338(1-2), 241-254.